Two years ago, I found myself reading about Seamless SSO (SSSO).

I understood the concept, but I always wanted to see what it actually looks like – and today is the day!

This post doesn’t present any new attack or groundbreaking concept.

It’s just me playing with SSSO, documenting the process, and sharing a mini abuse idea that (obviously) didn’t work.

Why?

Because I want to 😎

Let’s start at the beginning.

We all know the machine account AZUREADSSOACC.

We know it’s dangerous, right? It’s even in the documentation!

What’s the deal with delegation, you ask?

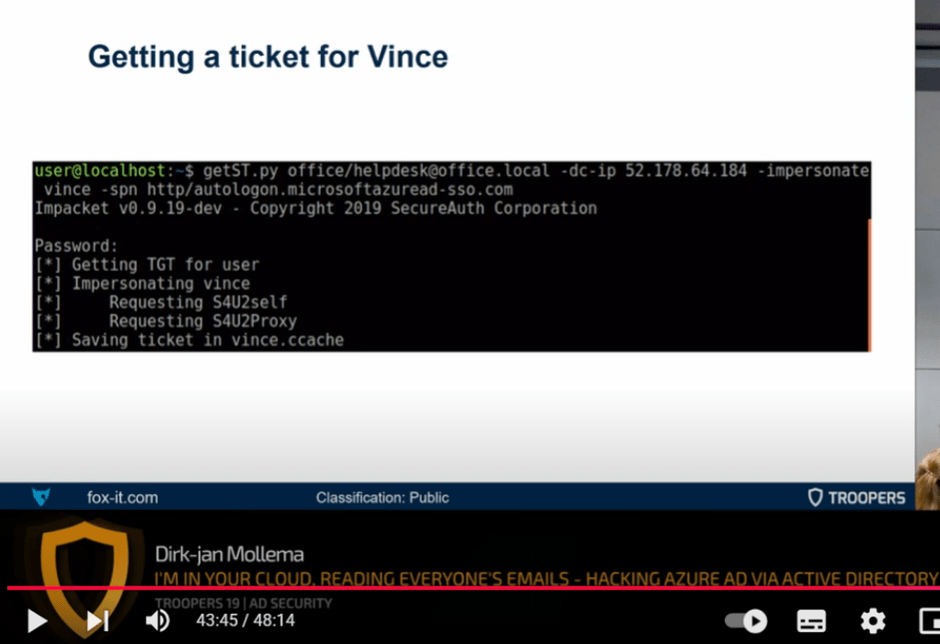

Well, that’s from Dirk-jan’s Troopers19 talk:

(BTW, go watch this talk.)

So why is getting a Service Ticket (ST) to AZUREADSSOACC interesting?

Because it basically equals cloud authentication.

We’ll soon see exactly how.

Now let’s configure SSSO and watch the authentication process – really see what’s going on under the hood.

What we need:

- A Domain Controller (DC)

- Entra Connect

- A tenant

- A domain-joined machine

- An Entra-synced user

I’ll skip the domain creation and Entra Connect configuration steps.

One quick thing: to turn on SSSO, you need to click “Enable single sign-on”:

You can also verify it’s enabled in the Entra Admin Center, under the Entra Connect tab:

Once Seamless SSO is enabled, the AZUREADSSOACC machine account is created on your DC.

One important thing to note is its SPNs:

One of them is the SPN used to get a ticket to the cloud – usually autologon.microsoftazuread-sso.com.

The concept:

If I log in with my synced Azure user to a domain-joined machine, and open a browser, I shouldn’t need to authenticate to Azure.

Here’s the flow:

- Sign in to the domain-joined machine with the Entra-synced user

- Open the browser (specifically:

https://myapps.microsoft.com/<tenant>) - ✨ Magic ✨

For this research I opened Wireshark and Burp on the domain-joined machine and navigated to https://myapps.microsoft.com/<tenant>.

Let’s see what happened.

Starting with Wireshark:

First thing I noticed is a TGS request to the SPN we saw earlier on AZUREADSSOACC.

After decrypting the encrypted part, I could see that the username was test_sync – my synced user that I signed in with.

- To decrypt Kerberos traffic, you can use this script to create a keytab:

👉 https://github.com/dirkjanm/forest-trust-tools/blob/master/keytab.py - And follow this guide:

👉 https://medium.com/tenable-techblog/decrypt-encrypted-stub-data-in-wireshark-deb132c076e7

Cool.

So the synced user has a TGS to the SSO SPN – now what?

Now I opened Burp:

I’ll skip over the less interesting stuff.

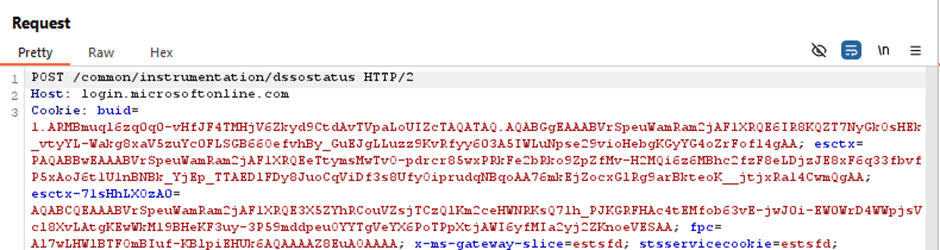

The main thing I saw was this request:

GET /<tenant>/winauth/sso

Host: autologon.microsoftazuread-sso.com

The payload looks like a Base64 value.

We’ll decode it in a second — don’t worry (:

The next requests:

Then:

And finally, the request we all know and love:

This one returns the access and refresh tokens. We’ll get back to those in a moment.

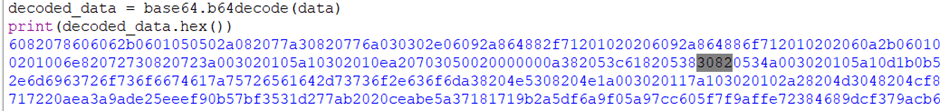

But first, let’s look at that base64 payload in the ../winauth/sso request:

After decoding it, I saw something very familiar…

Apparently, after you spend 3 months decrypting GSSAPI and decoding ASN.1, you know what it looks like 😅

Oh hey, Kerberos ticket (3082..)!

Trust me — I compared the hex.

This is the ticket inside the TGS_REP.

Now we understand that this TGS is all we need for authentication.

Which explains why configuring delegation on AZUREADSSOACC is dangerous.

All we need to forge a ticket to the cloud is the hash of AZUREADSSOACC.

(What an exhausting name.)

Fun idea time!

Based on Dirk-jan’s original idea, and a new vulnerability (DMSA) discovered by Akamai.

We can use the DMSA vulnerability to steal the hash of AZUREADSSOACC, and forge a ticket to the cloud for any synced user.

How?

In his findings, Yuval showed that by populating the msDS-ManagedAccountPrecededByLink of a DMSA object with another account, the PAC in the TGT will actually be the PAC of that linked account.

Another thing he discovered:

There’s a new structure in the TGT request called KERB-DMSA-KEY-PACKAGE.

It contains two fields: current-keys and previous-keys.

The previous key is the hash of the linked account’s password!

In our case — AZUREADSSOACC.

Which means… we can use it to forge STs as we like.

So — if you have permission to create or modify a DMSA — you can compromise an entire tenant.

What a small world.

Side note: I spent some time on it and it didn’t work. but it supposed to work. I’m pretty sure i just need to invest a bit more time.

Here is what i did:

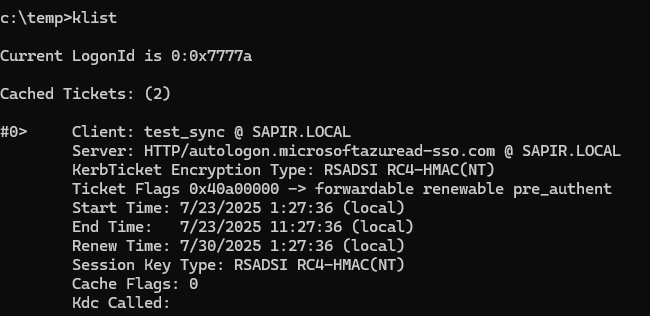

configured everything and got the RC4 hash of the AZUREADSSOACC:

Build a service ticket using that hash:

Then i hoped it will work, it didn’t. But it should, i will add here an update if I’ll ever succeed 😁

But okay, that’s not the topic of this post 😅

Let’s go back to SSSO authentication.

We got an access token. Let’s check it out.

We can see the onprem_sid, which indicates this is a hybrid account,

but other than that, there’s nothing to show that this was a Seamless SSO authentication.

Another thing I noticed — the scope.

Why do I have Application.ReadWrite.All permission?

That seems weird. I have zero roles.

I knew it was too good to be true, but just in case, I tried to add a password to an existing app — and got an “unauthorized” error.

The world makes sense again 🌍

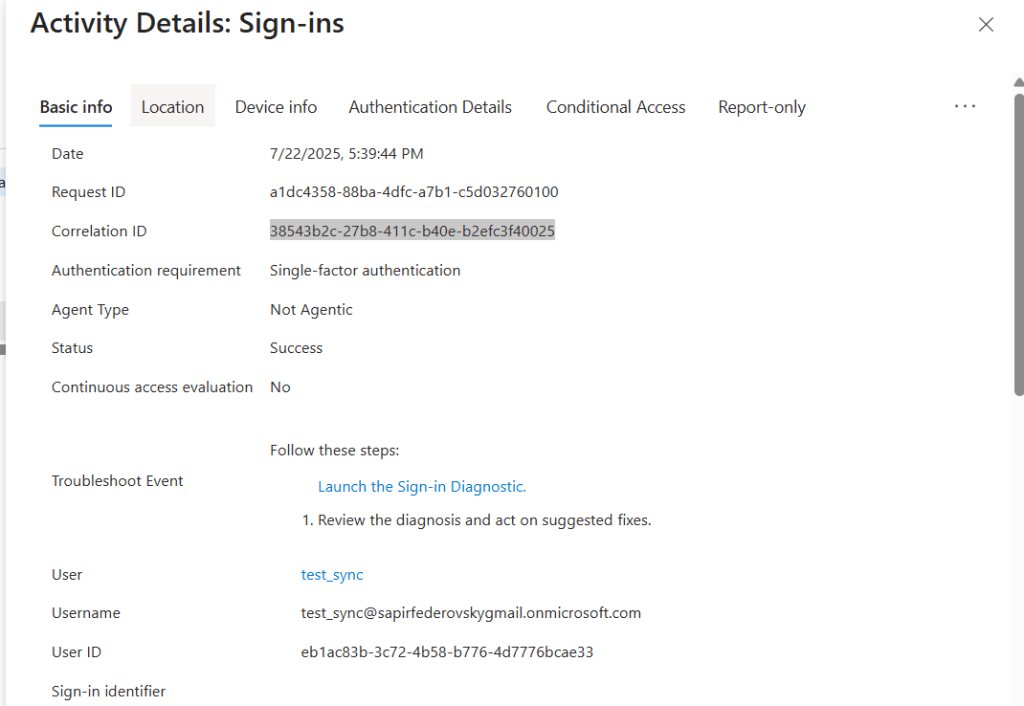

Last thing — sign-in logs:

Let’s see what we can find there.

I took the unique token identifier from the token and tried to correlate it with the logs.

To my surprise — there wasn’t a single indication that this authentication was via Seamless SSO.

Also, it was marked as Single-Factor Authentication.

To be fair, it kinda is — but the device also has to be domain-joined, which isn’t exactly “low bar” in terms of effort.

So, what can we say?

Stop using Seamless SSO.

Join or register your devices to Azure, work with PRTs — it’s much safer.

And if you still have AZUREADSSOACC in your environment…

please, make sure it’s protected, okay? (:

Leave a reply to sapir federovsky Cancel reply