Me and non-interactive sign-in logs had a rough start.

I used to think these logs were only relevant in one scenario:

When a refresh token is used to get a new access token.

And it made sense – after all, that’s something that happens without user interaction. No need to re-enter a username, password, or MFA.

BUT

Apparently, there are many other cases hiding in these logs.

And if you’re not aware of them, you might miss real attacks.

Don’t worry – I’m here to save you all the confusion! 😊

Let’s start with how to actually get these logs, because even that part can be a bit confusing.

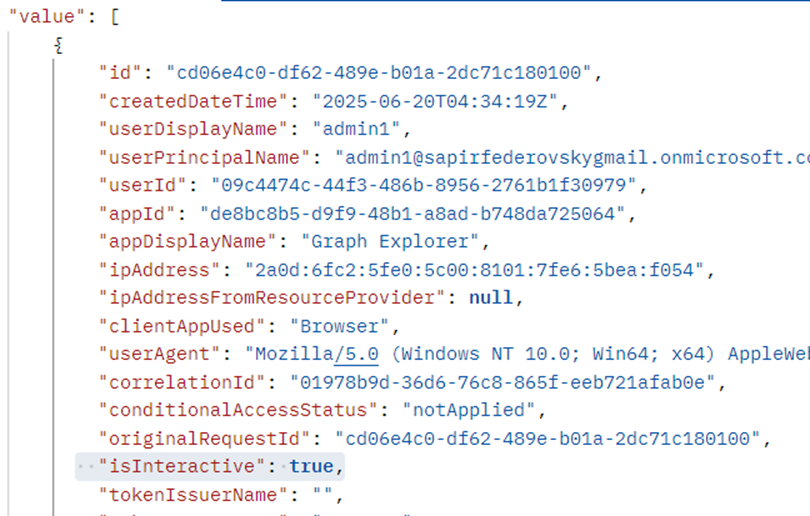

Do you remember this field in the sign-in logs?

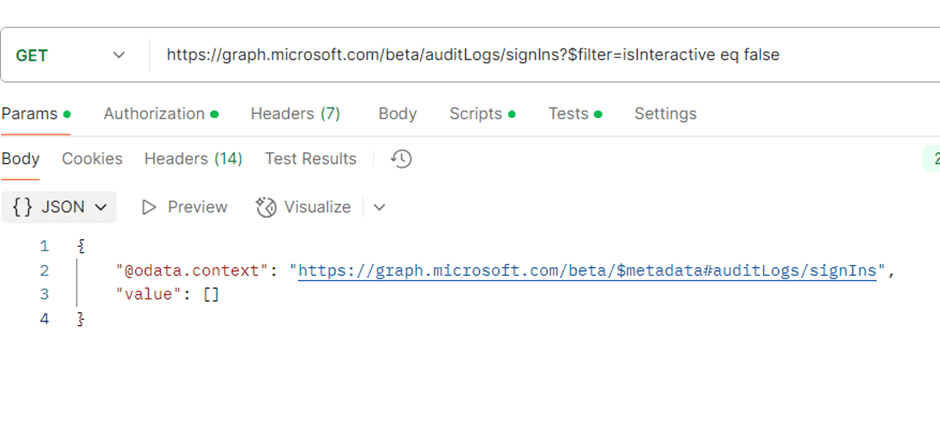

Well, I thought if we filter for false, we’d get the non-interactive logs.

Guess what? That’s not how it works.

So, what is the correct way to read the non-interactive logs?

Here’s the query you need:

https://graph.microsoft.com/beta/auditLogs/signIns?$filter=signInEventTypes/any(t:+t+eq+'nonInteractiveUser')

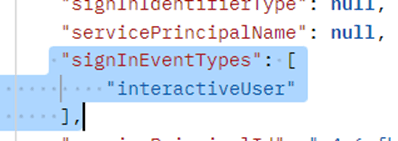

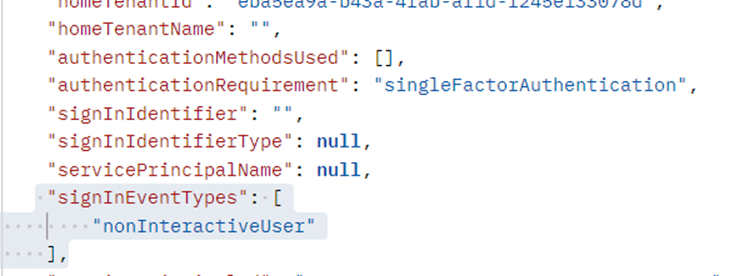

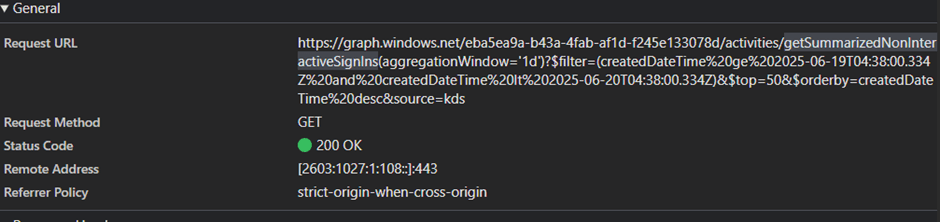

By the way, I tried checking the UI to understand how it reads these logs, and saw this:

Turns out, the UI is using the AADGraph endpoint to read non-interactive logs.

Anyway—now that we know how to read them, let’s talk about what’s actually in them.

According to Microsoft, these are the scenarios that generate non-interactive logs:

- A client app uses an OAuth 2.0 refresh token to get an access token.

- A client uses an OAuth 2.0 authorization code to get an access token and refresh token.

- A user performs single sign-on (SSO) to a web or Windows app on a Microsoft Entra joined PC (without providing an auth factor or interacting with a prompt).

- A user signs in to a second Microsoft Office app on a mobile device using FOCI (Family of Client IDs).

Now here’s the interesting part – some of these are cases where the user is actually doing something.

Not everything here is fully “behind the scenes”.

That means…

An attacker’s behavior might only show up in the non-interactive logs.

And here’s another thing:

These aren’t even all the scenarios that lead to non-interactive logs!

My journey started with this:

How weird is it to see a non-interactive log with a wrong password?

If it’s not interactive, how did the user even enter the wrong password?

What kind of scenario can cause that?

If you’ve ever seen this post about brute force attacks with a “fasthttp” user agent – this is that case.

So what do we have here?

- Non-interactive sign-in log

- “Other clients” client

- Error code 50126 (wrong password)

authenticationRequirement: singleFactorAuthentication

My first assumption?

This must be some kind of legacy authentication.

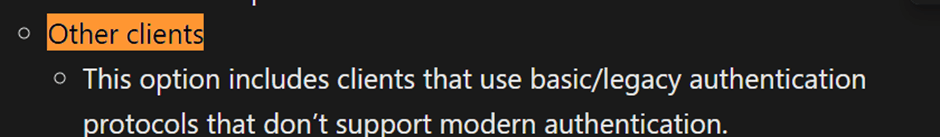

According to Microsoft’s documentation:

We now know we can detect this kind of brute-force behavior by simply searching for non-interactive logs using “Other clients”.

But to understand exactly which flow the attacker used… keep reading 😉

The key thing to understand about this attack is:

It’s not just hidden in the logs – it also bypasses MFA.

Why? Because basic authentication doesn’t support MFA.

While researching this case, I tried a bunch of legacy/basic auth flows.

But all of them showed up as interactive.

This is where I say thank you to @4ndyGit, who talked to Microsoft and helped us find the right direction!

The method used here was:

The RST2 flow.

Who’s familiar with this? I knew nothing about it!

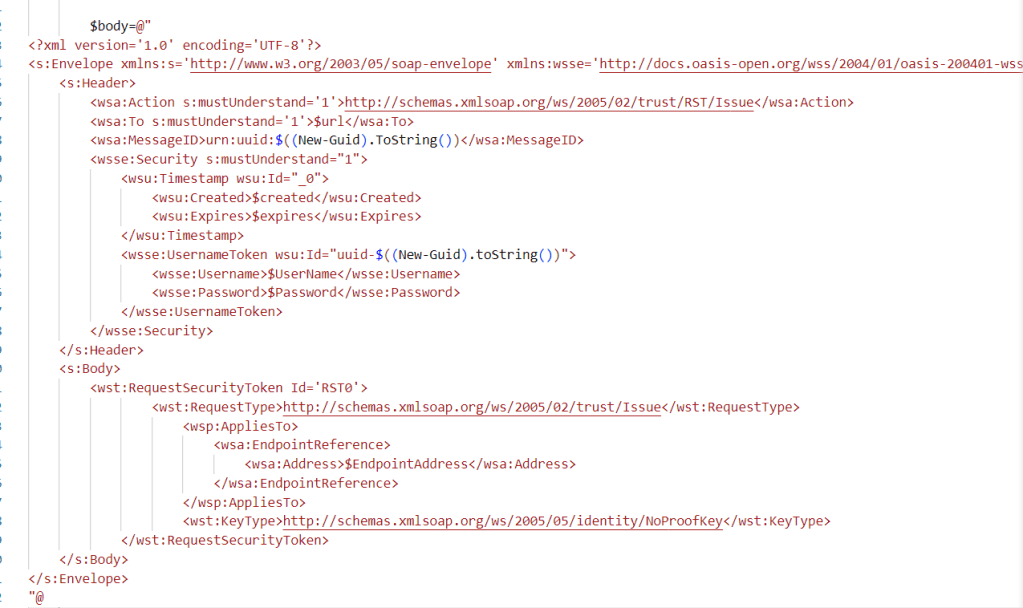

RST2 is a super old authentication method.

It’s not part of OAuth flows. It uses SOAP, and it allows basic auth – username and password in every request.

It’s considered deprecated, but it can still be used by some apps (like SharePoint).

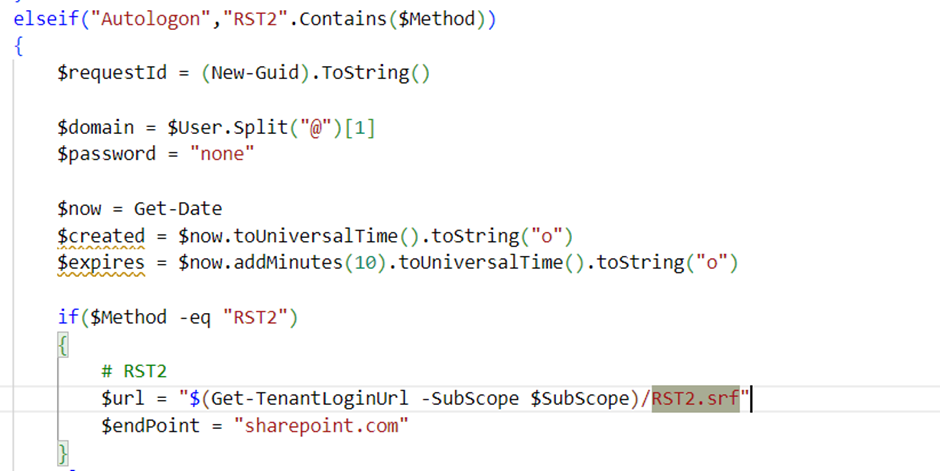

you can see how the SOAP request looks like in AADInternals:

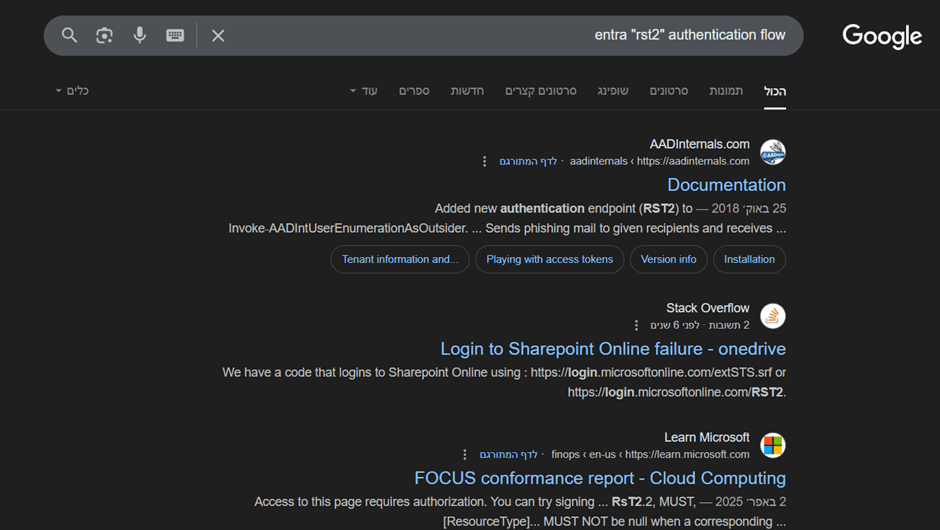

It’s kinda funny that I couldn’t find much about it in Microsoft’s docs—

but of course, I did find something about it in AADInternals!

Apparently, the Invoke-AADIntUserEnumerationAsOutsider function in AADInternals supports four auth flows—

and one of them uses the RST2 endpoint.

So to perform the attack, you can run:

Invoke-AADIntUserEnumerationAsOutsider -UserName <User>And that’s it!

Conclusion

It can be really frustrating to see behavior in the logs that you can’t explain.

This post shows the answer right away – but trust me, it took me a lot of time to get here.

Still, all the testing I did along the way taught me a ton. (:

Leave a comment