Introduction

We are well acquainted with the concept of log evasion in the world of endpoints—techniques such as running in kernel mode, using various APIs, hooking the logger, and more.

Now, the question arises: how can we achieve this in Entra?

To answer that, we first need to familiarize ourselves with the key players—the logs.

The Logs

I want to emphasize that the logs I am presenting belong to Entra. Let’s not forget that Azure has many other logs, which I will not cover here. 🙂

Sign-in Logs

I assume you are all familiar with these. However, there are still some important points to highlight.

Sign-in logs are divided into four categories:

- Interactive

- Non-Interactive

- Service Principal

- Managed Identity

It’s worth noting that the last distinction is somewhat odd, as a Managed Identity is essentially a type of Service Principal—but that’s the way it is, and we’ll work with it.

If we collect logs using EventHub, we’re good to go—all of these log types will be available.

However, if we retrieve them via GraphAPI, we must ensure that we use the Beta version.

This is because version V1.0 lacks a significant number of critical fields in the logs.

For example, non-interactive sign-in logs are not available in V1.0.

Audit Logs

These logs primarily document all actions performed within Entra. Examples include:

- Adding a password to a Service Principal (one of the most common persistence or privilege escalation techniques, in my opinion).

- Adding a user.

- Configuration changes.

- You get the idea.

GraphActivityLog

To be honest, I really like these logs. I always compare them to LDAP traffic logs in Active Directory.

Essentially, these logs document every GraphAPI request made in the tenant—both interactive and non-interactive.

For example, if I navigate to the Users section in the portal and add a new user, I will likely see a record of the corresponding GraphAPI request:

https://graph.microsoft.com/Users/…

However, there are some downsides to these logs:

- They generate a lot of noise—logging every GraphAPI call can be overwhelming.

- They require explicit configuration—unlike the previous two log types, if the customer does not enable this log, it will not be collected or sent.

- They require a P1/P2 license, or in other words—they cost money.

Despite these challenges, some companies utilize these logs. In my opinion, with proper research, they can be very useful for detecting attacks.

Objective of This Article

Now that we’ve covered the logs, let’s discuss how attackers might attempt to evade them.

But before diving in, let me reiterate the purpose of this article.

Log evasion in Entra is a relatively new field.

There have been some excellent research efforts on log evasion in AWS, but in Entra, there haven’t been any groundbreaking discoveries—yet.

So, why am I writing this article? Because I was eager to find new evasion techniques and hoped that writing about it would help.

But even if I don’t discover anything new, I still see great value in documenting my research process.

Maybe one of you will read this, gain inspiration from it, and succeed where I have failed. 🙂

General Concept

To bypass logs, we can use several techniques.

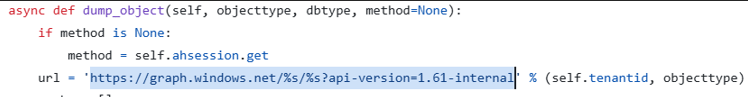

One of the most common is utilizing undocumented APIs that ultimately perform the same functions as GraphAPI.

You’ve probably heard of AzureAD Graph (https://graph.windows.net), which is an endpoint heavily used by Microsoft that allows performing the same operations as GraphAPI.

- I think Dirk-Jan initially discovered it

However, unlike GraphAPI, AzureAD Graph does not have a dedicated log that records every request!

So, if we want to perform enumeration, for example, using AzureAD Graph allows us to avoid being recorded in the GraphActivityLog.

Enumeration won’t generate an event in the Audit Log either, since we are only reading data and not modifying anything.

Therefore, the only way to detect this activity is by monitoring authentication to the AzureAD Graph client.

By the way, AzureAD Graph is set to be deprecated soon, which will likely lead to the discovery of new bypass techniques. 🙂

Let’s visualize this concept with an example:

Suppose I want to enumerate all users in an organization. I have two options:

- Use GraphAPI:

GET https://graph.microsoft.com/users

- Use the AzureAD Graph equivalent:

GET https://graph.windows.net/<TenantId>/Users?api-version=1.61-internal

Both calls will return the same data (and in some cases, the second call might even return more fields).

So, as an attacker, it is clearly preferable to use AzureAD Graph, which provides the information without leaving a trace in GraphActivityLog.

In fact, most attack tools leverage AzureAD Graph for gathering information.

For instance, the well-known tool roadrecon uses it extensively.

What Will We See?

We will see a sign-in log for the Microsoft Azure PowerShell client, as it is the only way to make requests to the AzureAD Graph endpoint.

As far as I know, this log cannot be avoided, and it does raise some suspicion (depending on the user, but generally speaking, this endpoint is deprecated and should no longer be in use).

This example illustrates my initial claims:

- It is very easy to evade GraphActivityLog.

- It is very difficult to evade other logs.

This means that the main scenarios we will discuss revolve around how to perform stealthy enumeration.

We can summarize the general concept as follows:

Finding APIs that return the same data as GraphAPI.

What Has Been Done So Far?

This post is based on 2 things:

1. The AMAZING work presented by @chrispy_sec in fwd:cloudsec talk

2. A very informative comment on my of my posts by @NathanMcNulty

So thank you both!

The APIs that have been discovered so far include:

Ibiza IAM

Endpoint: https://main.iam.ad.ext.azure.com/api This is essentially the Azure Portal API, the one used by the UI itself. See?

This API implements many calls that allow enumeration of the Entra environment. Here are two examples:

- https://main.iam.ad.ext.azure.com/api/Groups

- https://main.iam.ad.ext.azure.com/api/Roles/User/__USERID__/RoleAssignments

There is so much information that can be extracted about the tenant using these APIs that someone even documented them on a website:

👉 https://nodoc.cloud/ibiza-iam

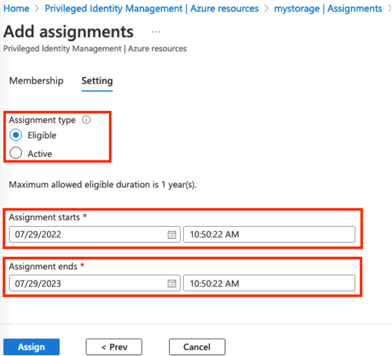

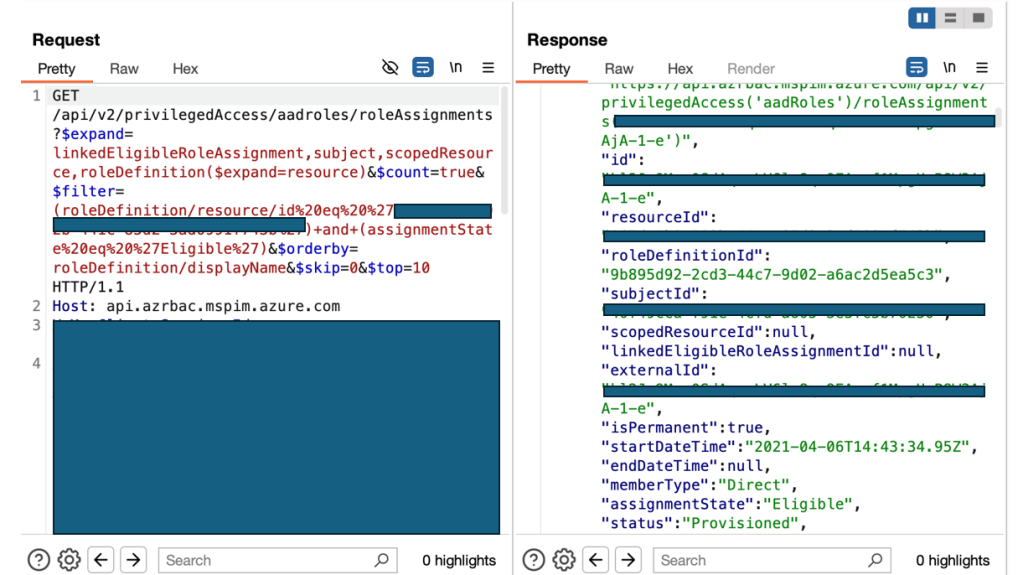

Our Second Endpoint: api.azrbac.mspim.azure.com

Whenever an API implements certain queries, there is usually a reason behind it. So, it’s worth understanding the purpose of the endpoint.

In our case, this is the API for PIM (Privileged Identity Management). Have you ever seen the Eligible Roles tab? Well, that’s PIM (or at least, part of it).

PIM is essentially a small security product that enhances security by controlling role activations.

Instead of permanently granting a user a role, you configure them as Eligible for that role.

For example, let’s say I have an IT admin who needs permission to reset all user passwords in the organization.

He definitely needs that permission—but does he need it all the time? No.

So, instead of granting the role permanently, I configure him as Eligible.

When he actually needs the role, he can go into PIM, click “Activate,” and—based on the configured settings—the role will be assigned temporarily and then automatically removed after a set period.

Now that we understand PIM, we can see why this API is useful—it allows us to enumerate Eligible role assignments inside the tenant.

Time to Try It Myself

At this point, I wanted to explore some new endpoints.

(They might not actually be new, but I don’t recall seeing talks or blog posts about them.)

I’ll explain what each endpoint does and highlight some interesting functions I found.

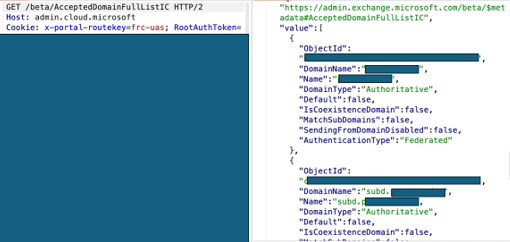

admin.cloud.microsoft

This API does not have a UI, meaning it is likely used internally by Microsoft.

It provides a lot of information, and here’s one interesting example I found:

GET /beta/AcceptedDomainFullListIC HTTP/2 This API returned all the domains and subdomains in my tenant!

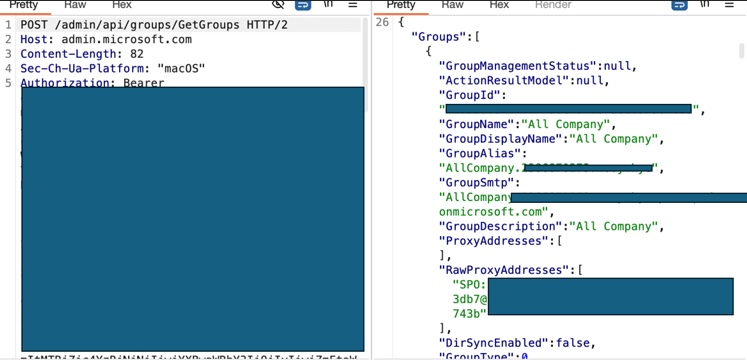

Moving on to Another Endpoint: admin.microsoft.com

This is essentially the Microsoft 365 Admin Center. Here, I found an API that returns groups, just like the /groups endpoint in GraphAPI!

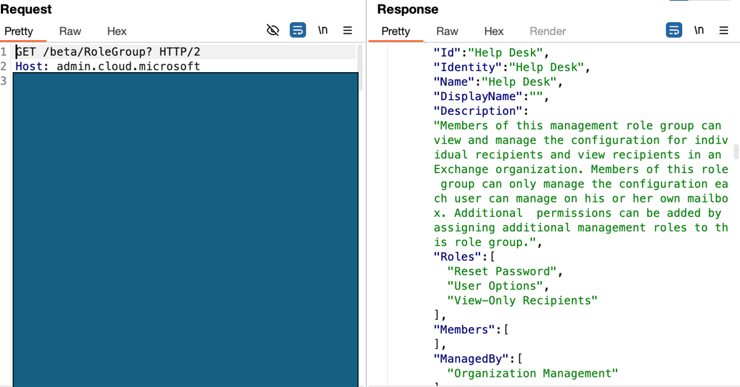

Additionally, I noticed an API called /beta/RoleGroup.

This call returned various role settings, but I’m not sure if they belong to Entra roles or not—so this might be beyond the scope of this article.

I also noticed that the response includes a list of members assigned to the role (though in my case, the list was empty, either because I hadn’t assigned the role to any users or because this isn’t actually related to Entra roles, and I don’t fully understand what I’m seeing).

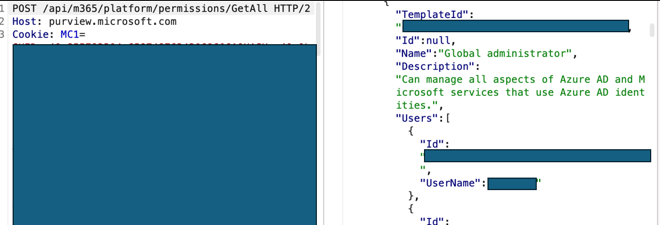

Another Endpoint I Found: purview.microsoft.com

Purview is a relatively new platform in Azure, designed to provide various data protection solutions.

To access it, you need an Entra user and, of course, a subscription—because nothing is free. One of the APIs I found there lists all roles in Entra and their assigned users.

Now, the question is: What do we see in the logs?

The Logs

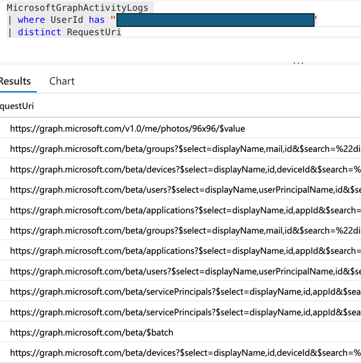

Using GraphActivityLog, I was able to see all the URIs I queried during my experiment. I was surprised to see so many URIs!

After all, the goal of this experiment was to avoid these logs.

Now, I needed to determine which endpoint I used during testing triggered GraphAPI queries behind the scenes.

This means that even though I used an API from a different endpoint, it’s possible that it internally made a GraphAPI call, which then got logged.

How Can We Identify Which Requests Came From Which Endpoint?

Surprisingly, we already have all the ingredients for this!

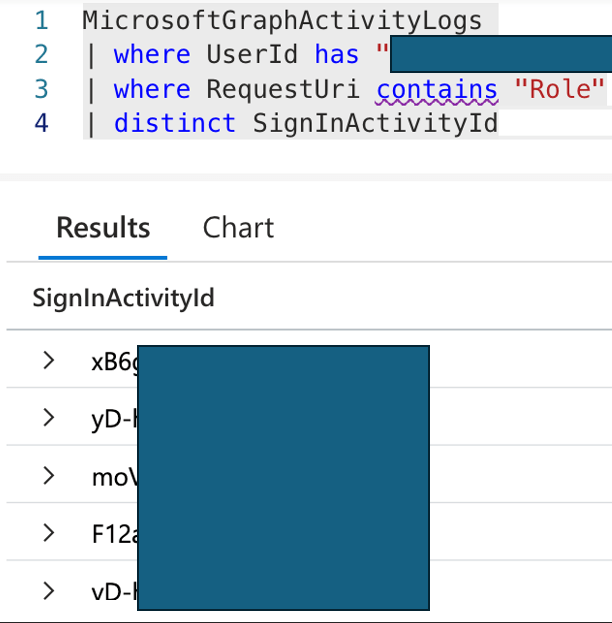

In GraphActivityLog, there is a field called SignInActivityId.

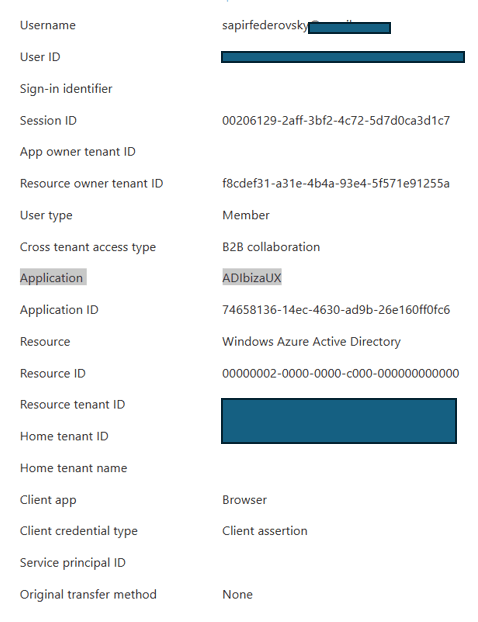

This field is identical to the Unique Token Identifier field in the Sign-in logs!

So, we can correlate which token request for which application caused these API calls.

No worries—it will all make sense with the screenshots 😊 Here is the SignInActivityId of the queries I suspected were logged during my tests:

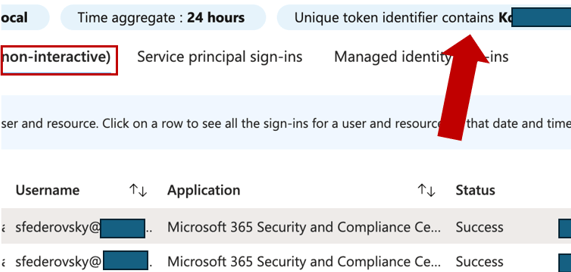

I then went to the Sign-in logs and searched for these values in the Unique Token Identifier field.

Key Observations

I highlighted a few things here:

First, inside the red rectangle, you can see that I am classified as non-interactive.

Why?

This type of log appears in several cases, including:

- Token Refresh – When an Access Token expires, the Refresh Token allows a new one to be issued without requiring reauthentication.

- Device Logins – Such as joined devices or Windows Hello for Business, which use tokens stored in the system.

- Single Sign-On (SSO) with PRT – Users already logged in with a Primary Refresh Token (PRT) on their device will have a new token issued automatically.

- Background Service Logins – Processes running in the background, such as Exchange Online, Teams, or Outlook, which retrieve data without requesting a password again.

- Silent Authentication with Cached Credentials – For example, when an application uses credentials stored in a Broker (such as WAM on Windows).

I assume that in my case, this was simply a token refresh.

(Generally, you can verify this using the incomingTokenType field. In my case, it was set to None, and since my machine is not joined and I wasn’t running a desktop application, a token refresh seems like the most logical explanation.)

Next, I checked the Sign-in logs for the applications where I found new APIs, such as Purview, and confirmed that no GraphActivityLog events appeared with my UniqueTokenIdentifier.

It’s a bit tricky to be 100% sure, as I ran many tests in a short period, but the findings seem to indicate that these APIs do not generate GraphActivity logs.

One possible exception is the admin.microsoft.com query—it may have been logged.

A More Elegant Way to Verify This? Use KQL!

There is actually a much better way to check this—using Kusto Query Language (KQL).

Here’s a query that should streamline the process. Of course, you can modify it to fit your needs. The main goal is to correlate the application I authenticated to with the GraphAPI query I executed:

let graphActivities = MicrosoftGraphActivityLog | where RequestUri contains "Roles" and UserId == "user_id" | project SignInActivityId, RequestUri; SigninLogs | where uniqueTokenIdentifier in (graphActivities | project SignInActivityId) | join kind=inner ( graphActivities ) on $left.uniqueTokenIdentifier == $right.SignInActivityId | project RequestUri, ApplicationWhat About the Data in the Sign-in Logs?

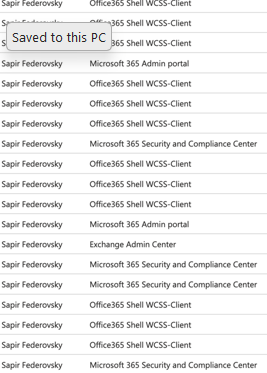

First, as I mentioned earlier, my tests generated a lot of noise. If we look at the logs, we can see this clearly:

There’s an interesting point here:

An attacker trying to bypass GraphActivityLog might use unusual APIs, like the ones I mentioned.

To do this, they would need to obtain a token for the applications exposing these APIs.

The process of obtaining this token will generate a Sign-in log entry, which could be considered suspicious on its own.

For example, if my company does not use Purview, it would look very odd if I suddenly authenticated to it for no apparent reason.

Should We Consider Detecting Anomalies in Application Sign-ins?

This really depends on the environment—the users, resources, and typical behavior.

However, in my small test environment, where a single user has only ever accessed Azure Portal, this definitely stands out.

So, even if some APIs allow you to evade GraphActivityLog, they might still trigger anomalies in the Sign-in logs.

What About Audit Logs?

For now, it seems that Audit Logs aren’t very relevant to this discussion.

The techniques I tested so far focus primarily on enumeration, not on actively modifying Entra.

Therefore, Audit Logs are less relevant in this context.

That being said! We know for sure that by using the AzureAD API (remember? We discussed this at the beginning), you can perform almost any action that GraphAPI allows.

These actions are logged in Audit Logs.

So far, I haven’t found (or seen documented) an API that allows modifications in Entra while bypassing audit logs.

(For example, I haven’t found an API that creates a new user without logging the event.)

Maybe this article will inspire someone to try and find one! 😊

Summary

The goal of this article was to document a light and enjoyable research experiment that could be done without too much hassle. I think we achieved that quite well—and even learned a few new things along the way! 😊

Evading cloud logs is a fascinating challenge. I assume that as detection capabilities improve, the need to hide better will also grow, leading to more research on APIs that enable this.

Hope I didn’t drive you all crazy! 😆

Leave a comment